davidpierce from nbc news in st peters

From NBC News in St. Peters’ Square, how our world has changed in one picture. Pretty unbelievable.

From NBC News in St. Peters’ Square, how our world has changed in one picture. Pretty unbelievable.

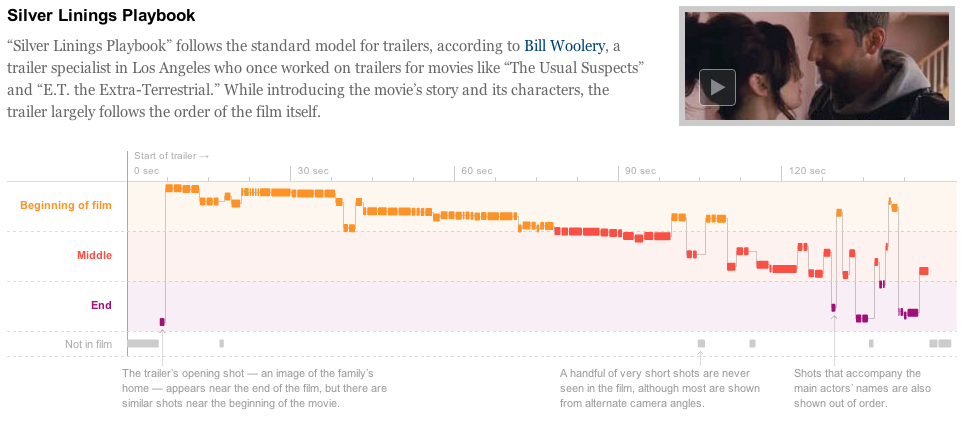

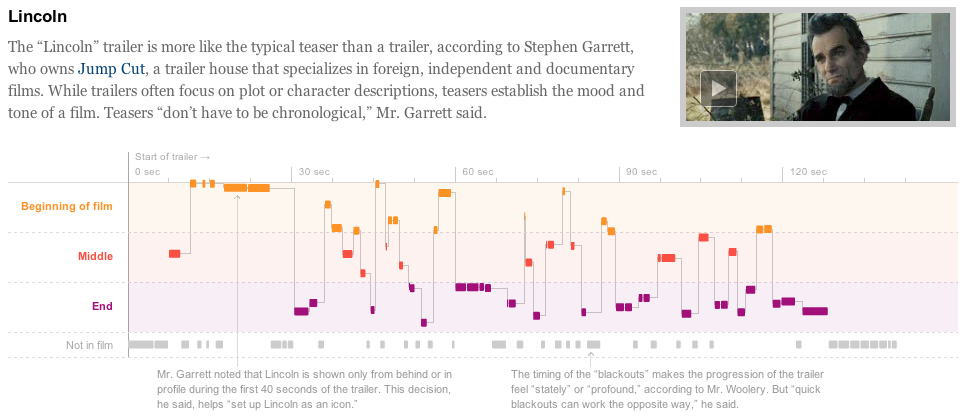

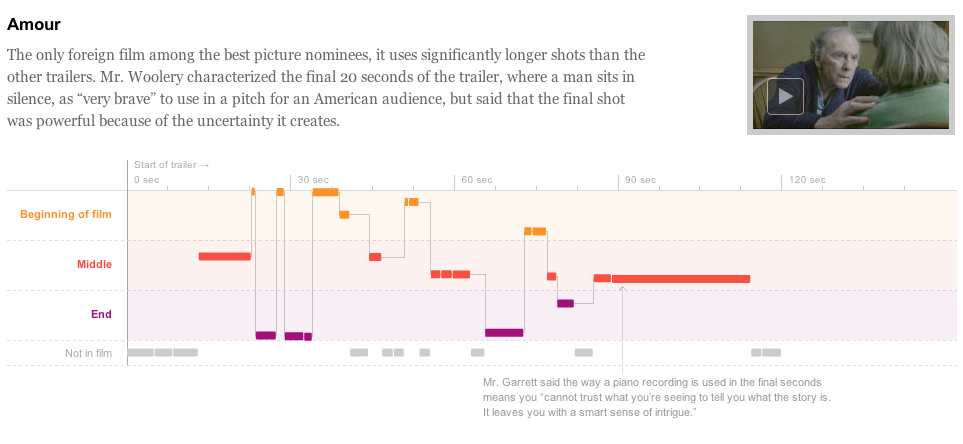

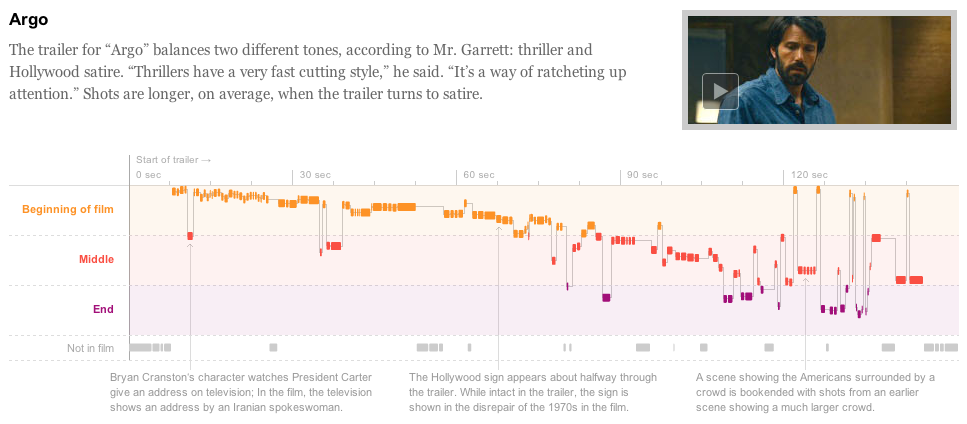

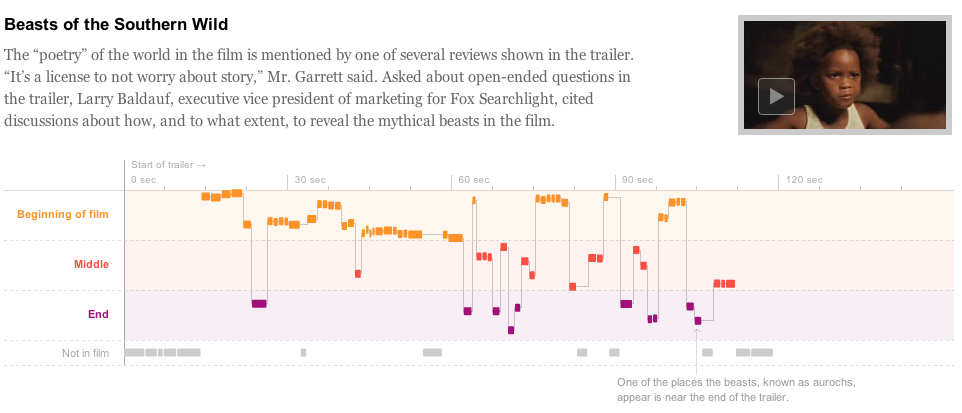

Dissecting a Trailer: The Parts of the Film That Make the Cut - Interactive Feature - NYT Graphics

How scenes from five of the nine best picture nominees were reassembled to promote the films.

Click through to inspect along each timeline. I’m sure we’ve all sensed some of these patterns in trailers but it sure is awesome to see it broken apart and annotated.

Incredible work. I love the use of data journalism in “soft” stories like this.

(If you back For Journalism, you can learn how to do this, too!)

Some of the smartest people working in data journalism today are going to teach you their secrets. Journerdalists from NPR, ProPublica, The New York Times, The AP, The Spokane Spokesman Review, and more will show you how to build a modern news app. Twenty bucks gets you started, a crisp benjamin gets you the whole course.

On its own, this is a great thing, I want it to do well, and I hope they can help educate the next round of hacker journalists.

Here’s why this is capital-I-Important, though, and why you might consider pitching in even if you’ve never considered an opportunity in the highly lucrative field of data journalism1. We are awash in “data”, some of which seems important, but most of which is so much flotsam. Data is powerful if we can translate it into information but it can also drown us if we just let it wash over. Or if we let corporations control it or use it to bully our cities and towns, or let governments get away with misusing it, or we just accept anecdote or conventional wisdom as truth.

The tools for working with all of this data are out there. There has never been a better time to dig into all of the numbers and systems that intersect with our lives every day. You can literally spin up a server for basically nothing and build a web app that real people can use. If you’ve ever had an idea for something that can better inform people about the world they live in, a hundred bucks and a few hours of your time will help you build it.

Places like NPR and The New York Times are always going to have smart folks working for them on the big stories, but they can’t be everywhere. We can, though, and with the right tools, we can be just as powerful.

actual lucrative career mileage may vary. The good news is, you’ll be able to sleep at night knowing you helped make the world a better place. ↩︎

Neither service is a lost cause. Yet. But both would be well served to revisit what made them special in the first place: engaging with peers, not merely consuming content from brands and celebrities; being a creative platform for developers; and championing social media where users, not advertisers, call the shots.

—

Why Fast Company doesn’t consider Facebook or Twitter amongst the most innovative companies.

As much as I agree, I just don’t see it happening. What they are describing here is social networking circa mid-2007, not 2013. It’s like pining for the old 5-cent store and soda fountain in an age of Walmart and McDonald’s.

I’m more than a little surprised by the sudden willingness to outsource publishing to what is at best a quasi-reliable, third party platform … at the end of the day news operations are being rebuilt around a company or two that seem largely disinterested in those very operations. To put it another way, imagine if there were only one network for email and one, albeit pretty cool, company controlled that. Would we be so excited about newspapers jumping on that trend?

—I was reminded of this thing I wrote this three years ago during yesterday’s Facebook brief outage. I continue to be surprised that companies not only rely on third parties like Twitter and Facebook but implement that integration in such a way when that third party goes down it breaks everything.

The expectations for a storage service are entirely different from those for a social network. Customers rightly “freak out,” as [Dalton] Caldwell [a founder of App.net] says, if an ISP tries to privilege certain kinds of data or if a storage service like Dropbox changes the privacy or licensing provisions in its terms of service. When Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram try to exert similar kinds of control, customers who do freak out are routinely told that they’re being irrational or that they had no right to expect any other kind of treatment from a free service that needs to be supported.

This may be odd, but it’s a combination of whether we see data as abstract or concrete, and the different ways we understand paid and free systems. Nobody’s evil, and nobody’s stupid, says Caldwell. (Well, maybe the anti-net-neutrality guys might be — ed.) It’s all just a natural consequence of companies’ business models and our evolving expectations toward payment and privacy on the web.

The expectations for a storage service are entirely different from those for a social network. Customers rightly “freak out,” as [Dalton] Caldwell [a founder of App.net] says, if an ISP tries to privilege certain kinds of data or if a storage service like Dropbox changes the privacy or licensing provisions in its terms of service. When Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram try to exert similar kinds of control, customers who do freak out are routinely told that they’re being irrational or that they had no right to expect any other kind of treatment from a free service that needs to be supported.

This may be odd, but it’s a combination of whether we see data as abstract or concrete, and the different ways we understand paid and free systems. Nobody’s evil, and nobody’s stupid, says Caldwell. (Well, maybe the anti-net-neutrality guys might be — ed.) It’s all just a natural consequence of companies’ business models and our evolving expectations toward payment and privacy on the web.

—Tim Carmody’s post on what app.net is becoming is really smart, even if you don’t care about app.net or what it’s becoming.

If she was indeed lip-syncing at the inauguration, give her the Nobel Prize in mime.

—Mike Doughty (yeah, that Mike Doughty) says Beyonce was singing live.

How much difference really is there between McDonald’s super-processed food and molecular gastronomy? I used to know this guy who was a great chef, like his restaurant was in the Relais & Châteaux association and everything, and he’d always talk about how there were intense flavors in McDonald’s food that he didn’t know how to make. I’ve often thought that a lot of what makes crazy restaurant food taste crazy is the solemn appreciation you lend to it. If you put a Cheeto on a big white plate in a formal restaurant and serve it with chopsticks and say something like “It is a cornmeal quenelle, extruded at a high speed, and so the extrusion heats the cornmeal ‘polenta’ and flash-cooks it, trapping air and giving it a crispy texture with a striking lightness. It is then dusted with an ‘umami powder’ glutamate and evaporated-dairy-solids blend.” People would go just nuts for that. I mean even a Coca-Cola is a pretty crazy taste.

—Jeb Boniakowski on why Times Square needs a McWorld.

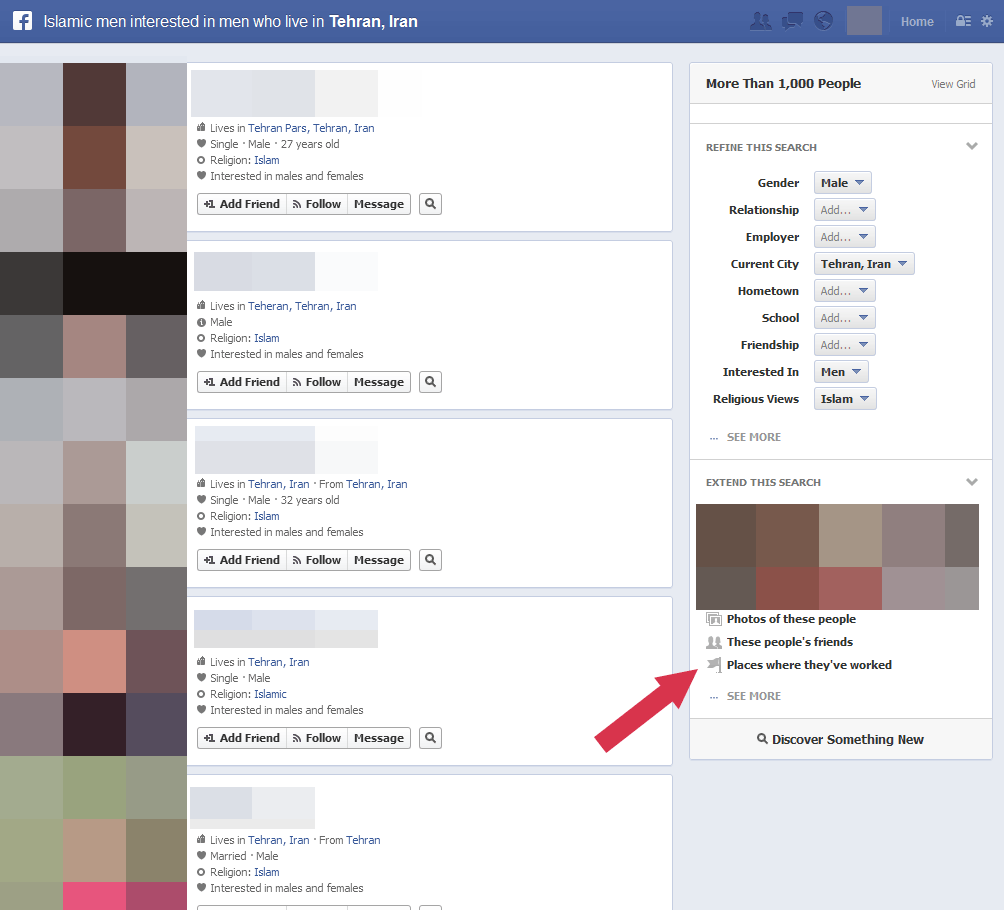

“Islamic men who are interested in men who live in Tehran, Iran”

BONUS: Extend this search to places where they’ve worked.

Just think, the world’s repressive governments want to block this.

More open and connected, indeed.

Facebook never wanted Likes to be objective indicators of real affection, or even a vague feeling of fondness. The Like button was designed as a marketing tool … It might seem kind of strange for a company to build a search engine — a pretty costly undertaking — using criteria that it knows to be debased, to be anything but objective. But to Facebook, it’s business-as-usual. Here’s the difference between Google and Facebook: Larry Page recognized that commercial corruption was a threat to his ideal. For Mark Zuckerberg, commercial corruption is the ideal.

—Nicholas Carr on Facebook’s polluted graph.